Two Yiddish Poets: Moshe Leyb Halpern and Avrohom Sutzkever

Moyshe Leyb Halpern (1886-1932), one of a group of gifted American-Yiddish writers who called themselves di yunge (the Young), lived during one of Yiddish poetry's most robust eras. An immigrant to America, Halpern worked at whatever job he could pick up during the day, and then would later meet his friends in cafés to discuss literary matters and share his literary work. With little money and less time, the young writers pulled together anthologies of their work and brought new life and energy to Yiddish literature.

Halpern was born in the city of Zlochev, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.He left for New York at the age of twenty-two. He began his career writing German verse but eventually was swept up in the high tide of Yiddish creativity that peaked around the early 1900s. Halpern was not a poet who contemplated the refined and the beautiful. "Much as I struggle only to see what is beautiful, I see only what is repulsive, a piece of rotten carcass." In some of his best poems, Halpern depicted the moral and psychic impoverishment of the immigrant masses. This theme is explored in realistic terms in "Around a Wagon":

There are people who maybe go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

But if it's nice to shlep in streets after a death wagon,

Clad in black, and lament with eyes sagging,

It is a sin to go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers and plums.

Perhaps one should not be so pushy, so attacking.

One can, perhaps, crowd quietly around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

But if you cannot chase them even whip wagging,

Because earth's tyrant, our belly, nagging,

Wishes so-you must be evil to go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

The writer seems to be suggesting that poetry, in particular, and refinement, in general, are inimical to the staccato rhythm of an immigrant population: their day-to-day behavior is propelled by nothing more than survival, by filling one's "nagging belly." But the poet suggests this with irony; his verse proves just the opposite. His poetry effectively gives expression to images of the common street, and does so in thickly colloquial speech. The street's chaos is punctuated by the recurring line a hawker shouts in the marketplace: "onions, cucumbers, and plums". The common and chaotic of the street yield to rhyme, rhythm and thrilling poetry. Moreover, the narrator warns the reader playfully not to pass judgment on the hungry crowds.

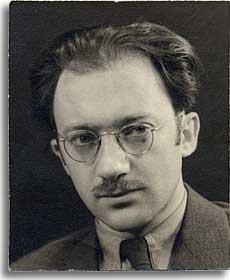

Avrom Sutzkever (b. 1913), is one of the most celebrated figures of the literary movement Young Vilna formed between World War I and World War II. While imprisoned in the Vilna ghetto after the Nazis occupied the city in 1941, Sutzkever and his colleagues risked their lives to smuggle hundreds of rare books and manuscripts away from Nazi destruction. Sutzkever wrote the following poem during the war, one that became a rallying cry among his fighting colleagues and friends:

The Lead Plates of the Rom Printers

Like fingers stretched out through the bars in the night

To catch the free light of the air that is shed-

We sneak in the dark to grab up, as in spite,

The Rom printing plates, with old wisdom inbred.

We dreamers now have to be soldiers and fight

And melt into bullets the soul of the lead.

The Rom printing press, most famous for publishing the classic edition of the Babylonian Talmud, as well as many Hebrew and Yiddish books, was an institution of Jewish intellectual life and civilization to which Sutzkever, as a poet, was devoted. The Nazis thrust upon the Jews a nightmarish reality that called for him and his friends to transform the power of the word into armed resistance. Sutzkever's continued poetic output during the war demonstrates that his resistance to Nazi barbarity took many forms. He taught poetry in the ghetto and joined a partisan fighting unit. Eventually he made his way to the safety of Moscow. After the war, he settled in Israel where he lives today.

Sutzkever's career since the end of the war has been marked by both mournful remembrance and renewal. In 1948 he founded the leading Yiddish journal, "Di goldene keyt " (The Golden Chain), which reestablished a literary Yiddish presence in Israel after so many of its writers were killed and literary centers destroyed. His powerful and exquisite poetry has led specialists to nominate him as a deserving candidate for the Nobel Prize.