Learn More About Yiddish Literature

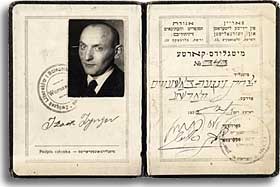

Isaac Bashevis Singer was one of four children born to Rabbi Pinkhes Menakhem and Basheva Zinger. Israel Joshua, his older brother, was the family rebel. He was a painter, fiction writer, and draft dodger. Hinde Esther, his older sister, was married off to a diamond cutter in Brussels, a man she had never set eyes on, because who else would want to marry an epileptic? She later got back at her parents by describing her sad life in works of fiction. Moyshe, I. B. Singer's younger brother, remained Orthodox and perished, along with his mother, in the Warsaw ghetto. And Itshele-Isaac? He, too, became a professional writer in Warsaw, joined up with his brother, I. J. Singer, who had emigrated to the United States, and ended up winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978.

For three out of four children in a single family to become successful writers is a bit unusual. But the mix of tradition and rebellion is not a bit unusual -not in the history of modern Yiddish literature. The first modern Yiddish storyteller was Reb Nahman ben Simcha of Bratslav (1772-1810), the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760). Reb Nahman was a rebel within the world of tradition. How else to explain his fantastically elaborated stories about abducted princesses, desert islands, enchanted forests, and crippled beggars? Sholem-Yankev Abramovitsh (1836-1917) on the other hand, started off as your typical Maskil, or reformer. After leaving home with a band of beggars and learning German from a private tutor, Abramovitsh turned against the leaders of the traditional Jewish community and the educators of their young. Then he hit upon a brilliant way of reaching the masses of Yiddish-speaking Jews, not by writing in his own angry, modern voice, but by inventing the character of Mendele the book peddler, who would do the talking for him. Yet alongside the many novels that Abramovitsh-Mendele produced in Yiddish and later in Hebrew, he also labored over rhymed Yiddish translations of the Jewish liturgy, for of what use were the prayers to God if the person praying didn't understand a word of them?

Another approach to combining tradition and rebellion was that of Yitskhok Leybush Peretz (1852-1915). Law rather than literature was his first choice of profession. After being disbarred, however, for reasons that remain hidden to this very day, Peretz began writing satiric poems and stories about the shtetl, like the famous "Bontshe the Silent," first published in a socialist newspaper in New York City. But when Peretz saw how quickly Jews were abandoning their traditions in the name of socialism, he launched a rescue operation, by turning back to hasidic teachings and medieval folktales.

Isaac Bashevis Singer combined all three models of revolutionary traditionalism. He began his career in the spirit of Abramovitsh-Mendele, producing harsh exposes of Jewish life in Poland. Then, in 1933, he wrote Satan in Goray, one of the first historical novels in Yiddish. Set in the 1660s in Poland, Singer brought Satan back, first in the guise of the false messiah, Shabbetai Zvi, then, at story's end, through a dybbuk (a wandering evil spirit). After immigrating to America, Singer was shocked to discover what had happened to his beloved Yiddish language in the streets of New York City and Miami Beach. And so, in 1943, he turned to the writing of monologues in the voice of the Devil, directly inspired by the stories of Nahman of Bratslav. If the Yiddish-speaking Devil couldn't talk some sense into modern wayward Jews-