The Roots: Synagogue and texts

No matter where Jews settled throughout the world in the Diaspora, they brought with them virtually the same collection of essential religious objects and other ingredients, and the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe were no exception. They carried with them their sacred texts, which helped them interpret the world they were living in within the tradition's framework of laws and wisdom. They brought with them the Torah  (Toyre in Yiddish), the five scrolls of biblical texts (what is also known as the Pentateuch), and Talmud

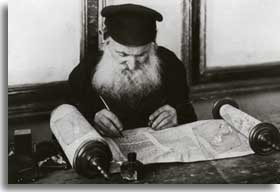

(Toyre in Yiddish), the five scrolls of biblical texts (what is also known as the Pentateuch), and Talmud  texts, which provide rabbinical interpretations of the Torah and elaborate on its many laws. These texts, handwritten on parchment, were sacred commodities and a special scribe (soyfer) was in charge of reproducing them as well as the newer rabbinic commentaries that were being added. The scribe's activity has always been seen as a religious undertaking itself for which a scribe was required to train not just in the art of calligraphy - for a text's accuracy and artistic reproduction - but also to understand and revere the actual meaning of the words.

texts, which provide rabbinical interpretations of the Torah and elaborate on its many laws. These texts, handwritten on parchment, were sacred commodities and a special scribe (soyfer) was in charge of reproducing them as well as the newer rabbinic commentaries that were being added. The scribe's activity has always been seen as a religious undertaking itself for which a scribe was required to train not just in the art of calligraphy - for a text's accuracy and artistic reproduction - but also to understand and revere the actual meaning of the words.

Equally important for Jews seeking to reproduce their culture and religious traditions in exile was the institution of the synagogue (shul in Yiddish), innovated by Jews to serve as a stand-in for the central Temple destroyed by Romans in Jerusalem in 70 CE. The synagogue, (a word of Greek origin, is known in Hebrew as a Bet Midrash (House of Learning), or Bet Knesset (House of Gathering) was an essential form of internal organization for Jews everywhere. The synagogue has always provided a social and communal context in which to explore and interpret the many intellectual themes and dictates of Judaism, as well as being a place to congregate, pray, and gather spiritual strength and emotional expression. The Jewish emphasis on learning, discussion, analysis, elaboration, and intricate intellectual dissection of ideas and religious texts were at home in the synagogue, and this mode of grappling with Jewish texts and Jewish ideas was extended to the yeshives  , the special Jewish academies of formal religious learning created throughout the scholastic centers of the Diaspora.

, the special Jewish academies of formal religious learning created throughout the scholastic centers of the Diaspora.

Orthodox Jews are required to pray three times a day. But the Sabbath, the weekly day of rest, which recalls the Creation of the World, which begins Friday night and ends at nightfall on Saturday, is the most significant holy and unifying day for all Jews. The Zionist writer Ahad Ha'Am suggested that, "more than the Jew has kept the Sabbath, it was the Sabbath that has kept the Jew." The importance of this day is established in the Ten Commandments; the symbolism of the day, its purpose and its ethic, are each a source of great inspiration and commentary throughout Jewish culture. The weekly Sabbath is the day that truly encompasses Jewish tradition, religion, culture, philosophy and ethics, sustaining the totality of Jewish life.