Where did Religious Jews Study?

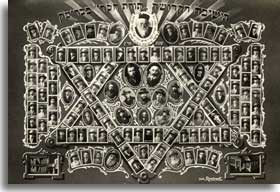

Yeshives  (Yeshivot in Hebrew). The institution of the yeshive dates back to the era following the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem, when the Jews gathered in the city of Yavneh and set up a new institution for the study of Jewish texts. This tradition of religious "universities" was brought to all points of the Jewish Diaspora, through Babylonian times, the Golden Age of Spain, and later on, in Eastern Europe. Different important Jewish centers housed distinguished yeshives throughout Eastern Europe, including the several internationally famous Lithuanian yeshives which came into being in the 19th century. After World War II some of the surviving representatives relocated their institutions to Israel and to the United States.

(Yeshivot in Hebrew). The institution of the yeshive dates back to the era following the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem, when the Jews gathered in the city of Yavneh and set up a new institution for the study of Jewish texts. This tradition of religious "universities" was brought to all points of the Jewish Diaspora, through Babylonian times, the Golden Age of Spain, and later on, in Eastern Europe. Different important Jewish centers housed distinguished yeshives throughout Eastern Europe, including the several internationally famous Lithuanian yeshives which came into being in the 19th century. After World War II some of the surviving representatives relocated their institutions to Israel and to the United States.

The formal "degree" necessary to obtain official recognition as a learned authority (Rabbi) is known as a smikhe. For some specialties, for instance to become a Dayan  ( a special type of judge within the Jewish court system), one needed to attain a few smikhes, each requiring years of text learning at the yeshive.

( a special type of judge within the Jewish court system), one needed to attain a few smikhes, each requiring years of text learning at the yeshive.

A Life Full of Traditional Elements

Jewish religious traditions and their structures have always been changing, yet not all changes rooted equally everywhere. The Reform movements in Germany, and the Neolog Conservative movement of Hungary, did not take wide root in Poland. In the larger cities there were Jews who supported some modern and Reform synagogues, still the Hasidic and Mitnagdic were predominant everywhere, especially in smaller towns. It is most important to understand that regardless of the level of religious observance, Jews in Poland-Lithuania lived within a cultural environment steeped in tradition. This reflected in Yiddish, the language all Jews used to communicate in. Look at any Jewish newspaper of the interwar period from Poland-Lithuania and you will notice the use of traditional metaphors in all types of article, regardless of the personal ideology of the writer. For instance, "Makhn shabbes far zikh" (to celebrate the Sabbath for oneself), described a detached, individual response where one was not expected. When a non-religious writer used that particular sentence, the literal religious association was not the meaning intended or communicated, but rather its social connotation. A Bundist or Zionist of any persuasion could use a phrase like this as they discussed their activities and not per se be thinking or employing religious imagery.

Ritual Objects in the Jewish home

Throughout Eastern Europe, a Jewish home could often be recognized by its location or the behavior and attire of its occupants, but certainly by a few special objects within. Candlesticks are the most recognizable and universal symbol of a Jewish table, next to the challah bread, but it is the mezuzah (a small, encased piece of parchment inscribed with a prayer and a blessing for those that come and go from that door), that is the most visible and external object identifying a Jewish home. The mezuzah is traditionally hung on the frame of any door of a Jewish home. The candlesticks, made of copper or perhaps silver, were essential for marking the commencement of the Sabbath and all holidays and were as necessary as the special kiddush cup for the blessing of the wine ( bekher in Yiddish). One could also find the embroidered challah cover (khale dekl in Yiddish); a menorah (the branched candelabra for the Chanukah holiday); perhaps some books, prayer books, or seyfers (religious texts used for learning), and more. These objects of representation and presentation - after all, the Chanukah menorah was to be displayed next to a window - were necessary implements for use in a Jewish home. The list extended (and still extends) to the tales (prayer shawl), the tales zekl (prayer shawl bag), and the tefillin (phylacteries). Jews used these items routinely for prayer and study, and likewise they came to be symbols of connection to their roots and to an ancient tradition. This was true even so for those that did not use them as often or on a daily basis.

In some of the more bourgeois homes there were beautiful items made of silk and silver, as well as special books and collections, which were either inherited through the family as heirlooms or bought as a wedding dowry when a couple started their own home. The craftsmanship of what today is called 'Judaica' (antique samples of these ritual objects)-displays the intricacy, variety, and creativity that went into making them. However, in the common home these critical Jewish objects were not always made of precious metals. Their value was really found elsewhere, in the meaning that emanated from these objects, which more than the wealth they could represent made them become such precious items in a home. We need to remember that the vast majority of Jews had simple versions of these objects in their homes - zeyer hob un guts (in their 'wealth') as mandated by their modest, and often poor economic resources. Inherited or bought, these Jewish ritual items represented intellectual and emotional connection to the Jewish community, past and present, as well as a way to frame their internal home environments with the symbols of Jewish tradition.