Modern Yiddish Literature.

Modern Yiddish literature developed at a fast clip, a characteristic common to many "minor literatures." An example of a major literature is French or English; each developed over hundreds of years, with a critical mass of readers and writers that was one of the largest in Europe. In contrast, Rumania or the Czech Republic possess "minor literatures" that began relatively later once writers of these nationalities began appreciating the distinctiveness of their cultures and languages and began writing in this spirit by emulating the products of major literatures. Likewise, modern Yiddish literature got its start at the beginning of the 19th century and spawned myriad literary styles and genres in a matter of just a few decades

Modern Yiddish literature was conceived under the influence of the Jewish Enlightenment movement in Eastern Europe that first began at the end of the 18th century. The Enlightenment Movement (Haskalah in Hebrew, in Yiddish Haskole) was an effort on the part of a group of enlightened Jews, called maskilim, to "reform" their Jewish brothers and sisters on a variety of levels with the intent to improve their lives and how they were perceived in the eyes of the world. They believed that Jews should dress more like their neighbors and shed their "Jewish clothing" (such as the caftan); they should learn more than just the rudiments of the surrounding language, should stop avoiding the country's school system in favor of a strictly Jewish education, and should choose more productive vocations. These issues and arguments animated the plots of the first examples of modern literature penned by maskilim. Too often the heavy-handed didacticism of these works eclipsed their literary aspirations.

Initially, the Haskalah had a very precise language program: its adherents believed that the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews should speak Russian, the language of their country, learn Hebrew as the national language of culture, and to shed or forget Yiddish-since they saw it as superfluous and a language with "little cultural value". What was the literary implication of this? Jewish writers should contribute to the growth of a Hebrew literature. And most maskilic writers began their careers writing in Hebrew. One of the greatest writers of the early maskilim was a schoolteacher named Sholem Abramovitsh.

My embarrassment was great indeed when I realized that associations with the lowly maid Yiddish world cover me with shame. I listened to the admonitions of my admirers, the lovers of Hebrew, not to drag my name in the gutter and not to squander my talent on the unworthy hussy. But my desire to me useful to my people was stronger than my vanity and I decided: come what may, I shall have pity on Yiddish, the outcast daughter of my people.

Abramovitsh's identification of the Yiddish language as a female, a "lowly maid" and "outcast daughter" was widespread among the maskilim who considered Yiddish inferior to Hebrew. At the same time, a group of them believed it was necessary to write Yiddish in order to teach the masses the lessons of the Enlightenment.

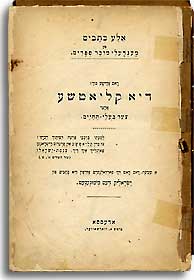

It might be due to this shame over writing in Yiddish that Abramovitsh wrote under the pseudonym Mendele-the-Book-Peddler. Throughout much of the 19th century, Jews living in the shtetlakh relied on traveling merchants to buy household items, ritual objects, and books. Capitalizing on the familiarity of a traditional peddler, Abramovitsh had Mendele introduce his stories of Enlightenment-stories that might otherwise have been spurned by most Ashkenazi Jews suspicious of Haskalah.

…I am called Mendele the Book-peddler. I am on the move most of the year; at one time I am here, at another there. I am known everywhere. I make my rounds throughout Poland and carry all sorts of books from the Zhitomir printing press. Aside from books, I carry prayer shawls, shofars, mezuzas. Sometimes you can also buy from me brass and copper wares… But this is beside the point. What I want to tell you has nothing to do with this. This year 5624 [1863-1864]-and it happened on Hanukkah-I drove to Glupsk where I counted on making a little sum by selling wax candles. Never mind, this too is beside the point. Arriving in town-it was Thursday, after the morning prayer-I drove, as I am used to, straight to the synagogue…