The Press

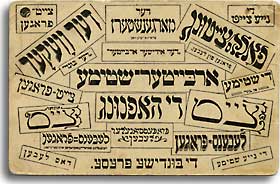

One of Warsaw's most fertile and dynamic institutions was its great Jewish press, through which the city's intellectual debate was concretely realized. The number of publications in Warsaw skyrocketed during the late 19th century - among both Poles and Jews - and constituted one of the highest concentrations of Jewish papers in the world. Dailies, weeklies, and journals, whether in Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, or German, were effective vehicles for expressing community ideas, politics, and ethnic identity.

In 1862, the first Hebrew paper, Ha-Zefirah (The Dawn) was established. It was also subtly secular and celebrated the resurgence of the Hebrew language. During its peak readership at the turn-of-the-twentieth century, Ha-Zefirah morphed into a popular Zionist organ. Another early weekly, Izraelita, published in Polish, appeared in 1866. But the true flowering of the Jewish press occurred along with the flourishing Yiddish culture and language, greatly boosted when Russian authorities loosened restrictions on the Press in 1905, just in time for the torrent of political dialogue that gripped all of the Jewish Eastern European world.

The first Yiddish daily was Der Veg (The Way), debuting in 1905, followed by the famously successful Yidisher Togblat (Jewish Daily Paper), which set the standard for popular Jewish newspapers. "The Togblat's two basic goals," Stephen D. Corrsin explained in his work on Warsaw's Jews before World War I, "were to be cheap (one kopeck), and to win readers through aggressive and lively reporting and sensationalism." In 1906, it printed "an average press run of 54,200 copies, which made it the most popular newspaper in any language anywhere in the partitioned Polish lands."

At the height of popularity of Warsaw's Yiddish press, the field attracted talented writers from many corners of the Jewish world, enticing journalists who were seeking to be a part of a great cultural elite, to join the ranks of artists, novelists, and intellectual bohemians.

Then and Now

Walking through Warsaw today, there are very few indications of the great Jewish presence that once made this city the premier destination for an emerging Jewish cosmopolitan class.

There is no Yiddish press, and there are no Yiddish writers. No Yiddish schools and no Jewish children. There is only a seasonal Yiddish theater performed by non-Jewish actors, an effort to pay tribute to a great institution that is no more. The Main Synagogue has been refurbished in recent years, after having been desecrated. A new museum, already under construction, is being erected in the plaza in front of the monument honoring the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto Jews, but the names of those who fought the ghetto battle are largely unknown to passersby. A walk through the sprawling old Jewish cemetery, which does remain almost intact, provides a glimpse of the colorful, and occasionally flamboyant, personalities that once resided side-by-side with the working-class Jewish masses in what was the most populous Jewish city in Eastern Europe. This is a lonely testament to the Jewish life that once thrived in Warsaw, a story that now continues with the remnant survivors now in other lands.