History and Settlement

When the Russians captured the Black Sea coast from a weakening Ottoman Empire in 1789, Odessa was but a small fortress overlooking a natural harbor. Once Tsar Alexander I recognized the economic and military potential of an Ukrainian port-city near such vast expanses of wheat hinterlands, the town grew at a breakneck pace. By the mid-19th century it had become the main port of entry for Asian goods into Europe, and a great center for wheat cultivation, processing, and export. Situated on a dramatic bluff overlooking the Black Sea, and surrounded by miles and miles of Ukrainian steppe, the cosmopolitan oasis of Odessa was a city of energetic industry and commerce defined by its grand scale and newness, a kind of Chicago of the East. An ethnic amalgam of Greeks, Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, Jews, and others, Odessa came onto the scene seemingly overnight. The city early on embraced the form of a modern and Western-leaning metropolis, a city not entrenched in Old World and medieval foundations. It was a city of great contrasts: liberal and modern yet host to some of the worst violence against Jews; diverse yet segregated; and containing ornate opera houses and Baroque palaces overlooking scrappy slums known for thieves and gangsters.

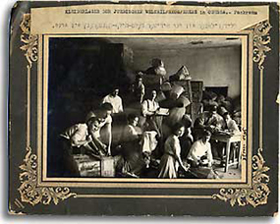

Jewish migrants flocked to Odessa in substantial numbers during the 19th century, seeking work, safety, and relative social freedom. At its heyday near the turn of the 20th century, Odessa boasted Europe's second-largest Jewish community after Warsaw, one that developed a rich secular culture of arts and letters, theater, and political activism. Upon arrival, many Jews initially staked out their standard roles as small-scale merchants and craftsmen. Hoped to gain a foothold in the lucrative wheat business, an industry in Odessa then commanded by Greek, Italian, and French companies.

Beginning as grain classifiers, sorters, and weighers, Jews gradually gained larger roles in the export business and, in a move that brought considerable hostility from competitors, in the 1860s broke the wheat monopolies, eventually achieving a dominant role in the trade. Jews also made up a major portion of those who worked in Odessa's liberal professions - in medicine, law, architecture - and formed a large industrial proletariat of factory workers and laborers.

In 1939, Odessa's Jewish community numbered some 180,000, about one-third of the city's population. The largest Jewish quarter in Odessa was the poor and overcrowded Moldavanska, a former suburb that once housed Russian military barracks. During the early 20th century the area contained rough slums notorious for gangsters, black-market swindlers, prostitution and other urban vices. A series of nearby limestone quarries offered secret catacombs for hiding stolen goods and contraband. These same catacombs were used and during World War II for hiding Ukrainian and Jewish partisans.