Songs and Anthems for Political Causes

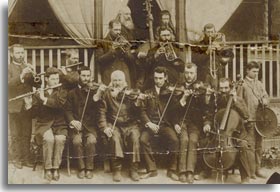

Eastern Europe was the birthplace of modern Jewish politics, and right from the start music played a significant role. Jewish labor activists and socialists used Yiddish songs to express their grievances and to recruit their fellow workers to their causes. Some of these songs were simply traditional Yiddish folksongs with new lyrics attached, while others used melodies from the popular marches and revolutionary songs of other Central and East European political movements. At political rallies, huge crowds of Jewish workers sang these songs together, often with brass bands accompanying them. Before World War I, workers' choruses also began to appear in Jewish urban centers across the globe.

The two most famous Jewish political anthems to emerge from Eastern Europe are the Zionist hymn Hatikvah ![]() ("The Hope") and the Bundist song, Di Shvue

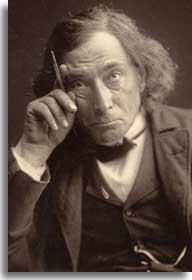

("The Hope") and the Bundist song, Di Shvue ![]() ("The Oath"). The Hebrew lyrics to Hatikvah were written in 1878 by Naphtali Hertz Imber, a Bohemian-born poet. The source of the song's melody has long been a point of controversy. Many have claimed it was based on a Moldavian folksong, while others suggested it comes from a symphony by the Czech composer, Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884). Still others maintain it is based on an old Sephardic religious melody. Whatever its true melodic source, Hatikvah became an instant favorite of the Zionist movement, and went on to become the national anthem of the State of Israel. Di Shvue was penned in 1902 by S. An-ski (Shlomo Zanvil Rapoport), the Russian Jewish writer. This Yiddish song, whose melody source also is unknown, exhorts Jews to unite, and to commit themselves body and soul to the defeat of the Russian Tsar and of capitalism.

("The Oath"). The Hebrew lyrics to Hatikvah were written in 1878 by Naphtali Hertz Imber, a Bohemian-born poet. The source of the song's melody has long been a point of controversy. Many have claimed it was based on a Moldavian folksong, while others suggested it comes from a symphony by the Czech composer, Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884). Still others maintain it is based on an old Sephardic religious melody. Whatever its true melodic source, Hatikvah became an instant favorite of the Zionist movement, and went on to become the national anthem of the State of Israel. Di Shvue was penned in 1902 by S. An-ski (Shlomo Zanvil Rapoport), the Russian Jewish writer. This Yiddish song, whose melody source also is unknown, exhorts Jews to unite, and to commit themselves body and soul to the defeat of the Russian Tsar and of capitalism.

Holocaust-Era Songs

During the dark days of the Holocaust, music was even more important to the Jews of Eastern Europe. For those Jews imprisoned in ghettos and concentration camps, singing Yiddish songs (both the newly composed and the popular prewar songs), was an essential element in maintaining psychological resistance and pride ![]() , as well functioning as a means of fostering some hope and happiness. Jewish partisan fighters wrote and sang songs to fortify their courage, and to celebrate "their victories" against the Nazis. These Holocaust-era songs are sad but moving testimonies to the deep soul, courage and determination of East European Jews throughout those times. After the war, these Yiddish songs remained as powerful symbols and memorials used for remembrance by Jews around the world. Many of these songs retain their powerful significance as anthems of the darkest period of Jewish history.

, as well functioning as a means of fostering some hope and happiness. Jewish partisan fighters wrote and sang songs to fortify their courage, and to celebrate "their victories" against the Nazis. These Holocaust-era songs are sad but moving testimonies to the deep soul, courage and determination of East European Jews throughout those times. After the war, these Yiddish songs remained as powerful symbols and memorials used for remembrance by Jews around the world. Many of these songs retain their powerful significance as anthems of the darkest period of Jewish history.

Contemporary Yiddish music

The musical traditions of Jewish Eastern Europe had already begun to decline in the late 19th century, due to emigration, industrialization, and acculturation. The tremendous destruction that accompanied World War I further displaced and eroded many portions of Yiddish life and culture, including the music. Moreover, during and after World War II, the devastation left by Nazi genocide against the Jews and the terrible postwar political repression in the Stalinist Soviet Union effectively crushed much of the remaining Jewish music and musicians in Eastern Europe. Yet beginning in the early 1970s, a new generation of young American Jewish musicians and scholars began to look beyond the Holocaust in search of the lost world ![]() of Yiddish culture. This huge renewal of interest in klezmer music and Yiddish folk songs, which began in the United States, quickly spread to Europe and beyond.

of Yiddish culture. This huge renewal of interest in klezmer music and Yiddish folk songs, which began in the United States, quickly spread to Europe and beyond.

Cultural activists, academics and artists joined together to bring to light old recordings made before and after World War I in New York, Budapest, Kiev and other cities. Old and forgotten musical manuscripts have been recovered and republished. Jewish musicians, both those who had emigrated to the United States several decades earlier, as well as the more recent arrivals in the waves of Soviet Jewish immigration during the late 1970s and 1980s, were interviewed in great depth, and their songs and biographies carefully recorded. The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research was a leading focal point for many of these intellectual efforts. In the mid-1980s YIVO began to sponsor annual retreats where musicians and other Yiddish enthusiasts gathered to teach each other, perform together, and dance to klezmer and other kinds of Yiddish music. Since that time, the popularity of Yiddish music has continued its tremendous growth among Jewish communities in North America, Europe, and the countries of the Former Soviet Union. More surprisingly, a huge non-Jewish audience has developed for this music in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, especially in Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland; the popularity of Yiddish music has continued to grow even in locations where few Jews have lived since the Holocaust.

Today's musicians employ a variety of creative approaches to traditional Yiddish music. Some artists focus on preserving older traditional styles of klezmer and Yiddish folk song through their performance and teaching. Others, like Israeli singer/songwriter Chava Alberstein, have extended these traditions by composing new Yiddish-language songs. Still others are engaging in wild new experiments in mixing ![]() Yiddish music with other contemporary kinds of music, such as jazz, rock, reggae, ska, and hip hop.

Yiddish music with other contemporary kinds of music, such as jazz, rock, reggae, ska, and hip hop.