Hasidic Music

One reason for the rapid growth and popularity of the Hasidic movement in Eastern Europe was its passionate belief that music itself was as vital and significant a way to pray as reciting the words in the prayer book. This emphasis on music and also dance as means to enhance spirituality and connect in a deep mystical way with God, led to the idea of the nigun, a wordless melody that is also a musical prayer. The nigun (melody, in Hebrew) was intended to transport its singers and listeners beyond the mundane worries of the world and into the realm of the spirit. A nigun was repeated over and over again until a sort of mystical harmony was achieved. In Eastern Europe, each Hasidic dynasty developed its own special styles of nigunim. Among the most admired were the Modzhitzer Hasidim, whose leader, Reb Yisroel of Modzhitz  , wrote hundreds of nigunim. Some people also considered him to be a great artistic composer in the classical music sense.

, wrote hundreds of nigunim. Some people also considered him to be a great artistic composer in the classical music sense.

The tradition of the nigun continues today, both inside and outside of the Hasidic world. In postwar America, the talented composer Shlomo Carlebach

![]() created a whole style of Jewish music virtually by himself, using some traditional Hasidic musical elements combined with American popular music, to create a neo-Hasidic style that has proven popular around the world and in Reform, Conservative and Orthodox Jewish communities.

created a whole style of Jewish music virtually by himself, using some traditional Hasidic musical elements combined with American popular music, to create a neo-Hasidic style that has proven popular around the world and in Reform, Conservative and Orthodox Jewish communities.

All Hasidic music was not strictly without words. Many Hasidic religious folk songs also appeared, with Yiddish and Hebrew lyrics, and sometimes both in combination. Some Hasidic songs even borrowed melodies and lyrics from Russian, Belorussian, Hungarian, and Ukrainian folk songs, adding Hebrew or Yiddish lyrics to turn the secular, non-Jewish songs, into a holy Jewish musical expression.

Yiddish Folk Songs

Yiddish folk songs began to appear in Eastern Europe not long after the Yiddish language itself. The medieval Yiddish folk songs that have survived are really long ballads, usually retelling epic stories of plagues, famines, and other dramatic historical events. Later Yiddish folk songs embraced a wider range of topics and featured everyday human emotions: young women's love songs, mothers' lullabies, children's play songs, men's drinking songs, and so on.

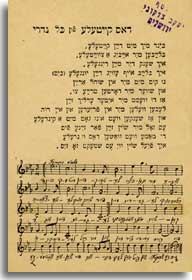

Some kinds of folk songs were sung by individuals, while others were intended for group singing or even to accompany young people's dancing. Songs were rarely written down or printed, although there were definite exceptions. The melodies of Yiddish folk songs came from a variety of sources, ranging from traditional synagogue motifs, to East European non-Jewish folk tunes, to European classical music.

Another important source of melodies for Yiddish folk songs was Jewish klezmer music; it was not uncommon for the same melody to be played as a klezmer tune without words for folk dancing, and also to be sung with words as a folk song ![]() .

.

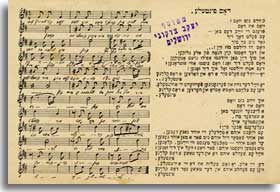

In general, Yiddish folk songs were passed on orally until the mid-19th century. Modern collections of Yiddish popular songs written by individual poets and composers then began to appear in print. These Yiddish popular songs eventually merged with the modern Yiddish theater, which once flourished in cities around the world. Much of this music was disseminated and distributed through the modern Yiddish recording industry, which produced hundreds of commercial recordings of Yiddish music, particularly in New York City, from the 1910s through the 1940s. Some Yiddish popular songs even crossed over into the American cultural mainstream. One example of a successful crossover is the 1934 American Yiddish theater song, Bay Mir Bistu Sheyn ![]() (For Me, You Are Beautiful). It quickly went on to become a national favorite in both the United States (in an English version) and in the Soviet Union (in a Russian version).

(For Me, You Are Beautiful). It quickly went on to become a national favorite in both the United States (in an English version) and in the Soviet Union (in a Russian version).