Czernica

One of the best accounts of village life that we have comes from a Jewish artist and Holocaust survivor, Toby Knobel Fluek, who painted and documented her community of Czernica in Poland (now within the borders of Ukraine). The Czernica of Fluek's childhood (the 1930s and 1940s) was a village of some 2,500 people, with a majority Ukrainian population, a large minority of Poles, and only about 70 Jews.

The tiny village had been her family's home for generations and they lived in relative isolation from Jewish community. Yet they survived as Jews over the generations. There was no synagogue, Jewish school, rabbi, or shokhet (ritual slaughterer); these necessities brought the family to travel to Podkamien, the nearest shtetl.

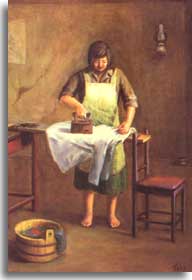

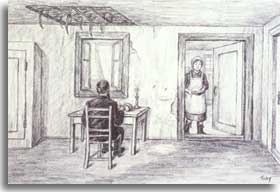

Fluek depicts in her drawings a daily life of limited resources and intricately complicated tasks: every bit of work required great preparation- there were no modern appliances for ironing clothes, baking, farming, or heating the small house. Fluek's father worked as a peddler and farmer, bundling and threshing wheat by hand with primitive scythes. During the best of times the family owned a horse and two cows.

Fluek's brother, Aron, was sent to Podkamien for Jewish schooling and visited Czernica only on holidays and special occasions. Their sister, Surcie, worked as a dressmaker from home, often taking in apprentices who lived and ate with the family. Toby Knobel Fluek remembers attending a Polish public school starting at the age of six:

"The school day began with a religious prayer, and the other children crossed themselves. I felt uncomfortable, and some of my classmates teased me, saying that I would have to cross myself too. That upset me very much; I was the only Jewish student in the school."

On the Sabbath, she was obligated to attend school, but opted not to do any work on that day.

Nevertheless, relations between the family and their non-Jewish neighbors were largely friendly. Fluek recounts how one neighbor, Katerina, and her children, helped with chores around the house, especially on Shabbos. In return, Fluek's mother offered some money and sewing work to the family. And, in the wintertime, her mother invited the neighbor peasant women to her house for a feather-plucking party:

"They sat around the table telling jokes and stories, having a good time while the work was done. Afterwards Mother served baked potatoes with herring. The feathers were used to make featherbeds and pillows. Pastry brushes were fashioned from goose and duck tails, and we made feather dusters from the wings."

In Czernica, as in every Jewish community, Shabbos was the focal point of the week. Fluek describes the routine preparations for Shabbat dinner: buying those grocery items not grown on the farm (oil, sugar, salt, pepper), painstakingly kashering the meat (chicken or beef), baking challah, and cooking the meal. "Friday afternoons the wood-burning oven was heated, and the cholent [stew] was placed there to cook overnight for the Sabbath meal. The house was cleaned, and everyone dressed in their good Sabbath clothes and freshly polished shoes."

For Fluek "Jewish Czernica", a place where only 10 scattered Jewish families lived (out of 100), where her parents home served as a makeshift synagogue, reflects the stubborn, rooted worldview these Jews carried with them. You can feel the rhythm of Jewish life in a small village through her drawings of Shabbos, holidays, and preparation of Jewish foods. Fluek's childhood world was not that of the Yeshive, day schools, and intellectuals, nor one including the contemporary political movements. Fluek's Jewish world was similar to that of the peasants, a life far away from the great urban hubs of the interwar period. She exhorts us to understand that rural Jewish life as she wants to remember it: as a life that to her was ideal until it was totally destroyed.